Fantasy is a funny beast (ironically). It’s easy to dismiss it as dragons ‘n’ arrows; the land of a thousand quests, where you can’t have a word without starting it with s. But when you find someone who gets it right, it’s like finding – oh, I don’t know – a mysterious golden ring or something far-fetched like that. It has a power that sucks you in.

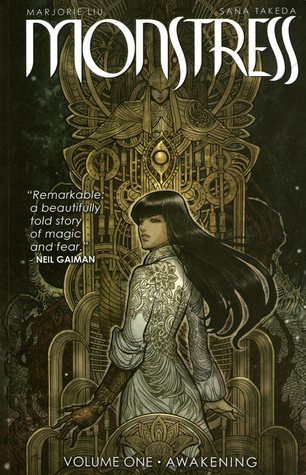

The Hugo award-winning Monstress is a fantasy graphic novel that does it right. The world-building is superb, leaving few cracks in its foundations, and you’re aware of the wider plot in the same way as, when you’re on a train, you’re aware of the rails.

That said, this isn’t for everyone. The world that Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda have painstakingly constructed is grim and gritty. In the words of a film about milkshake: there will be blood. There’s really quite a lot of it, revealed in all sorts of interesting and violent ways. There’s also a fudge-ton of swearing. These don’t feel particularly gratuitous, for the most part – they serve to ground you quickly, to help you figure out exactly what sort of world this is. Hint: it’s not Center Parcs.

One thing that’s immediately obvious is that this world is matriarchal. Almost every character in the book is a woman, barring a few non-descript guards and a couple of semi-major characters. It feels deeply refreshing to see women inhabiting a wide variety of roles within the story – villains, heroes, wrestlers, children, gods.

And these characters are filled with nuance. Our hero, Maika Halfwolf (which would win an award for ‘the most fantasy novel name ever devised’, but you quickly forgive it) isn’t a simple hero. She is impulsive, selfish and angry as well as driven, powerful and brave. This applies across the board – there are no moral black-and-whites here. Everything is on an ethical grayscale.

Takeda’s artwork is stellar, beautifully rendered, and drawn from both Eastern and Western influences to match the similarly-inspired dual sources of storytelling that Liu draws from. The detail is vivid and palpable. Her attention to focus is brilliant too – in frames with so much detail in can sometimes be different to know where to put your attention, but that’s never a problem in this.

This feels like the beginning of a much longer story, as you’d expect from a genre where a standalone novel is considered the outlandish freak cousin of the family. I’m definitely going to be following it.

--

This is my twenty-third book review of 100 to raise money for Refuge, the domestic abuse charity. If you liked this review, or just want to help out, please donate on the link below!

Comments

Post a Comment