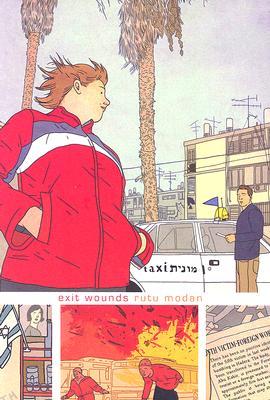

Rutu Modan’s Eisner Award-winning debut graphic novel, Exit Wounds, is troubling and sweet by turns. Set in Tel Aviv, it draws (indirectly, I hope) from her experiences of day-to-day there to explore what it means to be living in Israel, and to be Jewish, particularly as a woman.

This isn’t a book that contains violence – it contains the aftermath of violence, and the constant threat of it. The way death and destruction is normalised is skilfully done; a recurring motif is the way people respond to the protagonists’ questions about a recent bomb explosion by confusing it with another one that occurred afterwards. The implication is clear – here, explosions are normalcy. You only generally refer to the most recent one.

For all that, this isn’t a book about Israel and Palestine. It doesn’t seek to make Israel a victim, or Palestine an aggressor (or vice-versa), or even mention Palestine or Palestinians at all. This is a book about people who have learned to live in a context of regular violence, without invoking specific national politics.

Specific politics it does explore are those around gender. We see how women are encouraged to adopt American ideals of womanhood – make-up, ‘celebrity’-style clothes, even the trappings of an American teenage girl’s bedroom, as informed by imported films and television. For the main female protagonist, Nuni, pushed towards these aesthetics by her mother and contrasted with her happily-Americanised sister, it creates low self-worth. For the main male character, Koby, it’s a prejudice for him to overcome.

She also explores gender expectations in terms of how all the characters relate to their common denominator – the absence of Koby’s father. He is clearly a man going through an identity crisis following his wife’s death, but all we see is the trail of destruction he leaves as he tries on and abandons the various roles his culture demands of him – father, lover, pious man. His way to achieve this, by making the women in his life disposable, speaks volumes.

From an artistic perspective, the style is simple, verging on goofy at times. This really works with the complexity of the themes and narrative that’re being explored – the contrast makes for a nice balance.

This is a quick but deeply compelling read. It does a fantastic job of making you really feel immersed in a culture at great speed, by dropping in little details that contribute to a complex wider picture. And if this all sounds a bit miserable (sorry), there’s also a storyline that genuinely feels pleasing and heart-warming by the final pane. As a whole, it’s a real achievement.

--

This is my eighteenth book review of 100 to raise money for Refuge, the domestic abuse charity. If you liked this review, or just want to help out, please donate on the link below!

Comments

Post a Comment