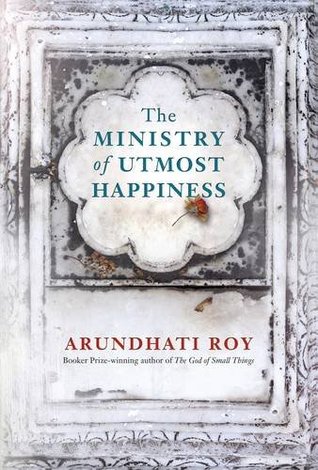

I loved The God Of Small Things like it were my own exceptionally eloquent child, and I raced through it. So I thought, I’ll read Arundhati Roy’s follow-up, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness - it’s thick, but I’ll get through it in no time. WRONG. I tracked through it like a lazy slug, and I’m now a whole book behind schedule! This is bringing out the fear-sweats no end.

But it’s worth it. TMOUH is an extraordinarily expansive and devastating book about the relationship between Kashmir, India and Pakistan over recent decades.

It’s a pretty big undertaking, at nearly 450 pages, but the reason for its size is its attention to detail. Every character gets a full story, a well of experience that Roy uses to make each one fully three-dimensional. At first this is confusing, because you struggle to understand who the main characters are, and what the primary story is. But after a while you come to realise that, despite having some key plotlines, the aim of this book isn’t primarily to serve up the narratives of individual people – it’s a character-study of three nations, conducted through those people.

And the picture it paints isn’t pretty. There are some upsetting things in here – it’s most certainly not a read for the faint-hearted. And the worst parts are the ones that are true. For example, the brutal and shocking attacks on Muslims in Gujarat in 2002 following a train fire that killed 56 Hindus. Or just some of the seemingly endless, heartbreaking massacres that have been perpetrated in Jammu and Kashir. Roy doesn’t spare the reader details, and the awful authenticity makes you flinch. She even charts the complicity of current Prime Minister Modi in many of these atrocities (of which I was totally igorant) – albeit disguising his identity so thinly that I did wonder why she took the effort to do so at all.

While the troubles have obviously been exacerbated, and to great extent caused, by the British carving up of India and Pakistan, actually this comes into the story very little. Western involvement is mostly shown as tedious naivety, with white activists and tourists serving really only to patronise and misunderstand the local situation. This is a book mostly focused on the present, rather than the past.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t give much hope for the future either. This isn’t an uplifting read. You feel a definite sense of despair in humanity, for its violence and inability to heal after conflicts, and its focus on power over prosperity. But then, a book about such divided and sad situations doesn’t owe its reader uplift – just authenticity. And you come away feeling you’ve been delivered that in spades.

--

This is my twelfth book review of 100 to raise money for Refuge, the domestic abuse charity. If you liked this review, or just want to help out, please donate on the link below!

Comments

Post a Comment